I first agreed to the medical mission trip this spring during our Nurse Practitioner white coat ceremony at Xavier. As far as I knew at that time, we were treating Malawian patients at four remote clinics who would normally not receive any form of healthcare. In the trip information it mentioned unfathomable volumes, extremely ill patients, and needed resources that were not readily available. I had my sight on a mission trip for quite some time, and this seemed like an appropriate scenario given my background working as an ER nurse and Trauma Program Manager for a busy rural hospital.

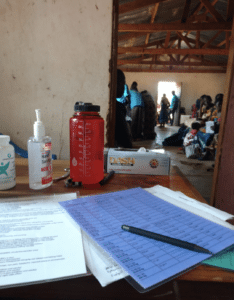

Set up and necessary preparations felt overwhelming as myself and other healthcare providers recognized a long list of drugs that we do not typically utilize in the United States, along with ones we did not have with us. Of course, we not only had to have a crash course on prescribing these foreign medications, we had to be able to recognize diseases such as Malaria, Shistosomiasis, and my favorite, gastrointestinal “worms”! It was quickly notable that the several veteran staff working with us have been experienced who guided us through the learning process, especially Lucy Goeke who was extremely knowledgeable and just a fantastic teacher.

I was assigned as a provider (or prescriber here) to the Nkumbira clinic, and the clinic days were very busy and could almost be recognized as slightly overwhelming most of the time. Throughout the three days we evaluated, treated, and provided medications to over 4,500 patient’s. The Malawi culture is one of dignity, respect, and civil fortitude. Well over a hundred patients were patiently waiting outside for us every morning with their medical passport- the only form of their medical record in their hands to openly share with strange providers. Not at any time were the patients disrespectful, have a sense of entitlement, nor demand any form of treatments and/or medications. Even though we were working under extreme pressure with providers we never seen before, each and every person walked into the clinic with the same goal to help make a difference in complete strangers’ lives, no matter how small.

The goal of the clinics is to do the most good for the most amount of people with limited resources. It was quite evident that a simple referral to the hospital was almost impossible for most, therefore all but life threatening cases needed handled in the one room clinic which did not have electricity nor running water. I will remember many cases forever, including those with a poor prognosis- knowing the feeling that some would not survive even with our best efforts will be there. The feeling of having to cut away dead tissue, make incisions and drain wounds without lidocaine or anesthesia just knowing that it has to be done to give patients a chance at beating infections. Finding recurrent Malaria in a child who’s spleen was so large it consumed a third of her abdomen, and feeling responsible to make the appropriate decisions in their care again to give them their best chance. Providing medications and draining infection from a foot to a child who could not walk due to the infection, having him return the next two days of clinic to see him walk again the last day. Seeing the comfort, joy and shear appreciation in the patients eyes each day made everything we did as a team made me feel overwhelmingly humble.

A quick shoutout should also be sent to Liz (Executive Director of VIP), Jordan (Liz’s daughter and extremely talented leader), and Lucy (Medical Team Leader and organizer) as none of the amazing work we completed as a team would have been remotely possible without you!

Walking into the Malawian airport, I didn’t know what to expect, what smells or what sights I’d be experiencing. I did not expect drawn on licenses plates or the forever lingering smell of fire wood. I would not expect the rocky roads that lead up to Namin’gazi Farm or the local food that would be made just for us. Not knowing a single thing about this country was intimidating and know where near comforting. Learning more about the team during debriefing after clinic began a strong connection that would help us during the three long and blurry days of clinic. Being a part of “support” staff added a feeling of incompetence within myself. However, during the three days, I have allowed myself to enter a different realm. Previously fainting from the sight of blood back home, I had been put to the limit while I ended clinic with cleaning wounds and dressing them. Though clinic was a blur, it has taught me the love of medicine and the memory has and forever will be connected with me. It has brought me self-confidence and has given me pure joy. The people of Malawi are driven to be faith driven and create a potential life changing feeling within each individual. They are brave, fierce, but have developed a sense of loyalty and devotion to God. They create raw emotion and unfiltered love; pure love. They can change your mind on life in less than an hour and create tears of uncertainty and joy. Being drawn to the people of Malawi is not a choice, but a must. Being in Malawi has not only brought me closer to God, but has developed a pure love for the Malawians and each profession in the medical trip.

Walking into the Malawian airport, I didn’t know what to expect, what smells or what sights I’d be experiencing. I did not expect drawn on licenses plates or the forever lingering smell of fire wood. I would not expect the rocky roads that lead up to Namin’gazi Farm or the local food that would be made just for us. Not knowing a single thing about this country was intimidating and know where near comforting. Learning more about the team during debriefing after clinic began a strong connection that would help us during the three long and blurry days of clinic. Being a part of “support” staff added a feeling of incompetence within myself. However, during the three days, I have allowed myself to enter a different realm. Previously fainting from the sight of blood back home, I had been put to the limit while I ended clinic with cleaning wounds and dressing them. Though clinic was a blur, it has taught me the love of medicine and the memory has and forever will be connected with me. It has brought me self-confidence and has given me pure joy. The people of Malawi are driven to be faith driven and create a potential life changing feeling within each individual. They are brave, fierce, but have developed a sense of loyalty and devotion to God. They create raw emotion and unfiltered love; pure love. They can change your mind on life in less than an hour and create tears of uncertainty and joy. Being drawn to the people of Malawi is not a choice, but a must. Being in Malawi has not only brought me closer to God, but has developed a pure love for the Malawians and each profession in the medical trip.

She wasn’t certain how old she was, but one of her middle-aged daughters, who lived nearby, told us that she thought that her mom was 89. We sat together on the ground talking about her life and everything that she had seen over the years. She told us that while she had endured drought and famine in her youth, she had no doubt that droughts were becoming more and more common in later years, a trend which both she and almost all scientists attribute to the effects of global warming. After talking for a few more minutes about the weather and how her harvest had been the last few years (2016 had been bad because of the drought, while 2017 had been better, though she was still anticipating running out of food before the next harvest) the talk moved to the children who had gathered around us.

She wasn’t certain how old she was, but one of her middle-aged daughters, who lived nearby, told us that she thought that her mom was 89. We sat together on the ground talking about her life and everything that she had seen over the years. She told us that while she had endured drought and famine in her youth, she had no doubt that droughts were becoming more and more common in later years, a trend which both she and almost all scientists attribute to the effects of global warming. After talking for a few more minutes about the weather and how her harvest had been the last few years (2016 had been bad because of the drought, while 2017 had been better, though she was still anticipating running out of food before the next harvest) the talk moved to the children who had gathered around us. VIP has given out LuminAIDs, which can be recharged each day and which will last for over 5 years, to top students for the past several years now. The LuminAID would allow him to read, study and see late into the night, something that we hoped would both reward, and allow for the continuation of, his academic success. As we handed it to him and showed him how to use it, he beamed with pride and happiness, thanking us for the gift and showing it off proudly to his grandmother, brothers and sisters and cousins and aunts.

VIP has given out LuminAIDs, which can be recharged each day and which will last for over 5 years, to top students for the past several years now. The LuminAID would allow him to read, study and see late into the night, something that we hoped would both reward, and allow for the continuation of, his academic success. As we handed it to him and showed him how to use it, he beamed with pride and happiness, thanking us for the gift and showing it off proudly to his grandmother, brothers and sisters and cousins and aunts.

She asked one of her daughters to mind the fire for her and came over to shake our hands and gestured for us to join her on a mat that she laid out for us, on the ground next to her home. As we talked, two kids sat down in mine and Tory’s laps. The boy who sat on Tory’s lap had been adopted by the young woman after his parents had died, but no one was sure where the little girl that sat on my lap had come from. I asked the woman if maybe she wanted to adopt her too, to which everyone politely chuckled. After talking for a few more minutes, and just when I had started to wonder if the little girl was potty-trained, I began to feel, with increasing horror, a wet spot growing on my pants leg. “I think she is peeing on my leg,” I whispered urgently to Tory, who immediately began to laugh. As I moved the little girl to the side and stood up I found that she had indeed peed on my leg, and soon everyone was howling with laughter. “It looks like you will be adopting her” Frank said to me as he patted me on my back and grinned.

She asked one of her daughters to mind the fire for her and came over to shake our hands and gestured for us to join her on a mat that she laid out for us, on the ground next to her home. As we talked, two kids sat down in mine and Tory’s laps. The boy who sat on Tory’s lap had been adopted by the young woman after his parents had died, but no one was sure where the little girl that sat on my lap had come from. I asked the woman if maybe she wanted to adopt her too, to which everyone politely chuckled. After talking for a few more minutes, and just when I had started to wonder if the little girl was potty-trained, I began to feel, with increasing horror, a wet spot growing on my pants leg. “I think she is peeing on my leg,” I whispered urgently to Tory, who immediately began to laugh. As I moved the little girl to the side and stood up I found that she had indeed peed on my leg, and soon everyone was howling with laughter. “It looks like you will be adopting her” Frank said to me as he patted me on my back and grinned.

Tory, Terra, Trudy, Sandra and John Anderson woke up early on Saturday morning as they accompanied Frank on a trip out to Mpoola village, the heart of VIP’s beekeeping initiative. VIP currently has 16 hives in Mpoola Village and when the beekeepers harvested in June, these hives produced enough for 25 bottles of honey. The honey was then sold to generate income for the beekeepers to spend on school fees, home improvements and further investments in their business. The Mpoola beekeeping project has become so successful that farmers in the nearby villages have expressed interest in becoming beekeepers as well. In June, Frank conducted a three day training session for two new groups from Ngomano and Liti villages so that they could learn how to care for hives and begin to enjoy all of the benefits that a healthy bee population can bless a community with. One of the best things about the June training session was that it was not just led by Frank and government officials. The experienced members of already existing beekeeping clubs volunteered their time so that they could help train other farmers as well. This is something that I noticed about VIP projects from the very start. People who have benefitted from VIP training and investment, do not try to jealously guard their position and hoard their knowledge, they become ambassadors for VIP, spreading knowledge and advice and even working alongside their countrymen, even if they don’t stand to gain anything themselves. This sense of community and generosity by ordinary Malawians marked every project that I worked on.

Tory, Terra, Trudy, Sandra and John Anderson woke up early on Saturday morning as they accompanied Frank on a trip out to Mpoola village, the heart of VIP’s beekeeping initiative. VIP currently has 16 hives in Mpoola Village and when the beekeepers harvested in June, these hives produced enough for 25 bottles of honey. The honey was then sold to generate income for the beekeepers to spend on school fees, home improvements and further investments in their business. The Mpoola beekeeping project has become so successful that farmers in the nearby villages have expressed interest in becoming beekeepers as well. In June, Frank conducted a three day training session for two new groups from Ngomano and Liti villages so that they could learn how to care for hives and begin to enjoy all of the benefits that a healthy bee population can bless a community with. One of the best things about the June training session was that it was not just led by Frank and government officials. The experienced members of already existing beekeeping clubs volunteered their time so that they could help train other farmers as well. This is something that I noticed about VIP projects from the very start. People who have benefitted from VIP training and investment, do not try to jealously guard their position and hoard their knowledge, they become ambassadors for VIP, spreading knowledge and advice and even working alongside their countrymen, even if they don’t stand to gain anything themselves. This sense of community and generosity by ordinary Malawians marked every project that I worked on. As we began to loosen the soil that had been packed around the timbers of the bridge since its construction we began to unearth all manner of dangerous creatures. The first animal we noticed was a particularly large centipede that crawled out of its burrow as the pickaxes began to crash through the soil around it. Centipede venom, particularly from larger species like this, can be extremely painful, though not generally fatal to humans.

As we began to loosen the soil that had been packed around the timbers of the bridge since its construction we began to unearth all manner of dangerous creatures. The first animal we noticed was a particularly large centipede that crawled out of its burrow as the pickaxes began to crash through the soil around it. Centipede venom, particularly from larger species like this, can be extremely painful, though not generally fatal to humans. After removing the two potentially venomous animals, for the safety of everyone involved, we were able to get back to work on the bridge, this time without incident. While we had been moving the timbers, a group of Malawians were digging a large trench in the mud near the river for the bridge’s supporting column. It was really striking to see two chiefs down in the trench, shoveling out mud and getting steadily dirtier, all for the benefit of their people.

After removing the two potentially venomous animals, for the safety of everyone involved, we were able to get back to work on the bridge, this time without incident. While we had been moving the timbers, a group of Malawians were digging a large trench in the mud near the river for the bridge’s supporting column. It was really striking to see two chiefs down in the trench, shoveling out mud and getting steadily dirtier, all for the benefit of their people.

These 16, representing all ages and genders, from a little girl of 10 to a host of elders 7 times her age, would form a new select choir. Enoch is not yet sure what this choir will become, but he knows that he wants to come back to Malawi and continue to work with them. His dream, still far off, is to find a way to get some of them over to the U.S., where they can perform in front of some of our church partners, allowing them to experience the beautiful and unique music that left Enoch literally speechless when asked later that day to explain his emotions on listening to the various choirs. Malawi does not have the same reputation for music that some of the larger countries on the African continent, like Nigeria and the Congo do, yet. But with the recent success of the Zomba Prison Project, a collection of prisoners and guards at the Zomba Prison whose first album was nominated for a Grammy, and the power of local Malawian choirs I am sure that is going to change soon.

These 16, representing all ages and genders, from a little girl of 10 to a host of elders 7 times her age, would form a new select choir. Enoch is not yet sure what this choir will become, but he knows that he wants to come back to Malawi and continue to work with them. His dream, still far off, is to find a way to get some of them over to the U.S., where they can perform in front of some of our church partners, allowing them to experience the beautiful and unique music that left Enoch literally speechless when asked later that day to explain his emotions on listening to the various choirs. Malawi does not have the same reputation for music that some of the larger countries on the African continent, like Nigeria and the Congo do, yet. But with the recent success of the Zomba Prison Project, a collection of prisoners and guards at the Zomba Prison whose first album was nominated for a Grammy, and the power of local Malawian choirs I am sure that is going to change soon.

It works like this: donors in the United States make a donation which provides a vulnerable family in Malawi with a goat. The vulnerable family cares for that goat and when it has its first kid, they pass the kid on to another vulnerable family and thereafter are free to make money selling the subsequent offspring to markets and other villagers. The families that receive the “pass-on” goats from their neighbors follow the same course, and slowly but surely the gift of one goat from one donor spreads throughout an entire village. One beneficiary of this program had sold over 16 goats after receiving her gift of a single goat, and has completely transformed the standard of living of her entire family.

It works like this: donors in the United States make a donation which provides a vulnerable family in Malawi with a goat. The vulnerable family cares for that goat and when it has its first kid, they pass the kid on to another vulnerable family and thereafter are free to make money selling the subsequent offspring to markets and other villagers. The families that receive the “pass-on” goats from their neighbors follow the same course, and slowly but surely the gift of one goat from one donor spreads throughout an entire village. One beneficiary of this program had sold over 16 goats after receiving her gift of a single goat, and has completely transformed the standard of living of her entire family. Others were bleating plaintively, over and over again, and if you closed your eyes for a second, it almost sounded like little children crying out for help. Realizing that this work needed to be done quickly, but carefully, for the well-being of all involved, and so that the children leading the goats could make their way to school in time for the closing day ceremonies, Frank gathered everyone around him to tell them what we were doing today and to issue instructions. The team members would fill up syringes with the appropriate amount of liquid medicine and then, with the help of the VIP staff, the goat owners, and the local committee members who had helped to organize this event, try to get the goats to swallow it.

Others were bleating plaintively, over and over again, and if you closed your eyes for a second, it almost sounded like little children crying out for help. Realizing that this work needed to be done quickly, but carefully, for the well-being of all involved, and so that the children leading the goats could make their way to school in time for the closing day ceremonies, Frank gathered everyone around him to tell them what we were doing today and to issue instructions. The team members would fill up syringes with the appropriate amount of liquid medicine and then, with the help of the VIP staff, the goat owners, and the local committee members who had helped to organize this event, try to get the goats to swallow it.

When the last of the goats disappeared down the trail leading away from the CBCC our battered team was able to catch its breath and take stock. The team was covered in regurgitated medicine, goat saliva, and dirt and, in the case of Robbie, several goat bites. But the program had been a success and all of the goats that had been signed up had received their deworming medicine and would be safe from parasites for the year.

When the last of the goats disappeared down the trail leading away from the CBCC our battered team was able to catch its breath and take stock. The team was covered in regurgitated medicine, goat saliva, and dirt and, in the case of Robbie, several goat bites. But the program had been a success and all of the goats that had been signed up had received their deworming medicine and would be safe from parasites for the year. The playground had been built by VIP with funds raised from a very special person. Megan Smith, a teacher at Allentown High School, located across the street from the VIP office, visited Malawi in 2011, after VIP founder Liz Heinzel-Nelson had come to speak at Allentown High School and had inspired Megan to go on a Friendship Trip with VIP. Megan was stunned by the scale and intensity of the poverty she encountered, and when she returned home she made sure that her kids understood how incredibly fortunate and privileged they were. Megan’s youngest daughter Ailey was particularly struck by how different life was for kids in Malawi. Hearing that kids in Malawi didn’t have any toys, and that they had to make soccer balls out of plastic bags stuffed inside each other and wrapped up with string, was a big shock. Ailey decided that she was going to do something about it. She told her Mom that she didn’t want any presents for her 8th birthday or for Christmas, any money that was going to be spent on her should be donated to VIP instead, so that we could build a playground for the kids in Malawi. Ailey asked her family and friends to help her and even made flyers and went door to door, asking people to help her raise money for the kids in Malawi. She had soon raised enough money to build an entire playground, and last year the VIP staff built it in Ngwalangwa village, telling the kids about Ailey and naming it Ailey’s Playground.

The playground had been built by VIP with funds raised from a very special person. Megan Smith, a teacher at Allentown High School, located across the street from the VIP office, visited Malawi in 2011, after VIP founder Liz Heinzel-Nelson had come to speak at Allentown High School and had inspired Megan to go on a Friendship Trip with VIP. Megan was stunned by the scale and intensity of the poverty she encountered, and when she returned home she made sure that her kids understood how incredibly fortunate and privileged they were. Megan’s youngest daughter Ailey was particularly struck by how different life was for kids in Malawi. Hearing that kids in Malawi didn’t have any toys, and that they had to make soccer balls out of plastic bags stuffed inside each other and wrapped up with string, was a big shock. Ailey decided that she was going to do something about it. She told her Mom that she didn’t want any presents for her 8th birthday or for Christmas, any money that was going to be spent on her should be donated to VIP instead, so that we could build a playground for the kids in Malawi. Ailey asked her family and friends to help her and even made flyers and went door to door, asking people to help her raise money for the kids in Malawi. She had soon raised enough money to build an entire playground, and last year the VIP staff built it in Ngwalangwa village, telling the kids about Ailey and naming it Ailey’s Playground. As I watched the kids swinging and sliding away happily, I knew that Ailey’s gift had been warmly appreciated by the children of Ngwalangwa and I couldn’t wait until Ailey got the chance to come see it for herself. In the meantime, Ailey has already begun fundraising for a second playground, so that kids in another village can have a fun place to just be a kid.

As I watched the kids swinging and sliding away happily, I knew that Ailey’s gift had been warmly appreciated by the children of Ngwalangwa and I couldn’t wait until Ailey got the chance to come see it for herself. In the meantime, Ailey has already begun fundraising for a second playground, so that kids in another village can have a fun place to just be a kid.

As the student’s names were announced, in order of their class rank, they calmly walked up and stood in line, but their parent’s reactions were anything but calm. When they heard their child’s name called, signifying that they had passed and did not have to repeat, they would shout and run up to the front of the crowd with their arms raised, often times ululating. If they caught their child on the way up to the line they would pick them up, plant a kiss on their cheeks, and carry them the rest of the way. They would give their child a gift, usually some corn chips, a soda and a few kwacha, hug and tip the teacher and then make their way, still celebrating, back to their seat, so that the next parent could celebrate their child’s passing.

As the student’s names were announced, in order of their class rank, they calmly walked up and stood in line, but their parent’s reactions were anything but calm. When they heard their child’s name called, signifying that they had passed and did not have to repeat, they would shout and run up to the front of the crowd with their arms raised, often times ululating. If they caught their child on the way up to the line they would pick them up, plant a kiss on their cheeks, and carry them the rest of the way. They would give their child a gift, usually some corn chips, a soda and a few kwacha, hug and tip the teacher and then make their way, still celebrating, back to their seat, so that the next parent could celebrate their child’s passing.

VIP has been providing scholarships for talented students for years. Our staff, particularly Maxwell Muhiwa, VIP’s Education and Vocational Skills Officer, identifies talented and hardworking students from a young age, and if they do well enough on their examinations, VIP provides them with a scholarship so that they can attend top government secondary schools, which, coming from the villages, they would not be able to afford on their own.

VIP has been providing scholarships for talented students for years. Our staff, particularly Maxwell Muhiwa, VIP’s Education and Vocational Skills Officer, identifies talented and hardworking students from a young age, and if they do well enough on their examinations, VIP provides them with a scholarship so that they can attend top government secondary schools, which, coming from the villages, they would not be able to afford on their own. He did exceptionally well on his examinations, and is now a top 5 student at his government run secondary school. He proudly told us that he had recently been accepted in to the Yale Young African Scholars Program, run by Yale University. The Yale Young African Scholars Program is a high-intensity academic and leadership program designed for African secondary school students who have the talent, drive, energy, and ideas to make meaningful impacts as young leaders, even before they begin their university studies. Yale African Scholars brings together students from across Africa in a seven-day, residential program and introduces them to the demanding U.S. university application process and requirements. Chimwemwe, who told us it too was his ambition to become a doctor, will be attending the all-expenses paid program in Zimbabwe, from August 18th to the 24th.

He did exceptionally well on his examinations, and is now a top 5 student at his government run secondary school. He proudly told us that he had recently been accepted in to the Yale Young African Scholars Program, run by Yale University. The Yale Young African Scholars Program is a high-intensity academic and leadership program designed for African secondary school students who have the talent, drive, energy, and ideas to make meaningful impacts as young leaders, even before they begin their university studies. Yale African Scholars brings together students from across Africa in a seven-day, residential program and introduces them to the demanding U.S. university application process and requirements. Chimwemwe, who told us it too was his ambition to become a doctor, will be attending the all-expenses paid program in Zimbabwe, from August 18th to the 24th.

Joining them from Texas were the four Andersons, Gayle, Phil, John and Nicole, who had come to Malawi four years ago, again at Randa’s urging, and who were coming back as a family for the first time since then. Gayle had been so moved by everything that she had seen and experienced on her first trip to Malawi with VIP, that she quickly became a Board Member, and has been an indispensable asset to VIP since then, using her years of experience as the CFO of major companies to expertly steer our Finance Committee.

Joining them from Texas were the four Andersons, Gayle, Phil, John and Nicole, who had come to Malawi four years ago, again at Randa’s urging, and who were coming back as a family for the first time since then. Gayle had been so moved by everything that she had seen and experienced on her first trip to Malawi with VIP, that she quickly became a Board Member, and has been an indispensable asset to VIP since then, using her years of experience as the CFO of major companies to expertly steer our Finance Committee.

Hailing from even closer to home was his roommate Enoch Smith Jr. Enoch is the music director at Allentown Presbyterian Church, where Stephen is the pastor and where the VIP offices are located. In addition to his role with the church Enoch is a professional musician and music producer and he had come to Malawi to organize a large choir competition and to connect with our Malawian friends through the universal language of music.

Hailing from even closer to home was his roommate Enoch Smith Jr. Enoch is the music director at Allentown Presbyterian Church, where Stephen is the pastor and where the VIP offices are located. In addition to his role with the church Enoch is a professional musician and music producer and he had come to Malawi to organize a large choir competition and to connect with our Malawian friends through the universal language of music. Rounding out our team was my new roommate, Hastings Machingili. Hastings is a child of two worlds, born in the United States to Malawian parents, he has spent large parts of his life in both countries. His father, Ramsey, is a successful Malawian businessman with a real heart for the work of VIP. Ramsey has partnered with VIP many times over the years, most recently as the renter of the VIP built maize mill, to help ensure that the mill is run efficiently and for the benefit of the community, while also providing income to VIP, which can be fed back into community projects, like building, and purchasing supplies for, CBCCs, which will be discussed in some detail below.

Rounding out our team was my new roommate, Hastings Machingili. Hastings is a child of two worlds, born in the United States to Malawian parents, he has spent large parts of his life in both countries. His father, Ramsey, is a successful Malawian businessman with a real heart for the work of VIP. Ramsey has partnered with VIP many times over the years, most recently as the renter of the VIP built maize mill, to help ensure that the mill is run efficiently and for the benefit of the community, while also providing income to VIP, which can be fed back into community projects, like building, and purchasing supplies for, CBCCs, which will be discussed in some detail below. Regardless of what they look like from the outside, CBCCs are some of the most important structures anywhere in Malawi. Studies show that human brain development and growth is most rapid and vulnerable from conception to age 5, and is largely influenced by aspects such as nutrition, caregiver interactions and household environment. As a result, the experiences and interactions of children during this period fundamentally shape their growth and lifelong prospects, making early childhood the most critical period of human development. Failure to develop properly during early childhood can lead to long-term, sometimes irreversible effects. Unfortunately, Malawi does not have a nation-wide pre-school program. So most children in Malawi are not receiving the stimulation and interactions they need at this critical point in their lives. That is why VIP is partnering with, supplying, and helping to organize more local CBCCs. CBCCs are run by community members, usually the mothers of young children who are volunteering to help out, and they serve as de-facto preschools to help ensure that children develop properly and receive the mental, social and physical stimulation they need to reach their full potential in life.

Regardless of what they look like from the outside, CBCCs are some of the most important structures anywhere in Malawi. Studies show that human brain development and growth is most rapid and vulnerable from conception to age 5, and is largely influenced by aspects such as nutrition, caregiver interactions and household environment. As a result, the experiences and interactions of children during this period fundamentally shape their growth and lifelong prospects, making early childhood the most critical period of human development. Failure to develop properly during early childhood can lead to long-term, sometimes irreversible effects. Unfortunately, Malawi does not have a nation-wide pre-school program. So most children in Malawi are not receiving the stimulation and interactions they need at this critical point in their lives. That is why VIP is partnering with, supplying, and helping to organize more local CBCCs. CBCCs are run by community members, usually the mothers of young children who are volunteering to help out, and they serve as de-facto preschools to help ensure that children develop properly and receive the mental, social and physical stimulation they need to reach their full potential in life.

Joined by Enoch and Tory, who had come from the CBCC open house, our group spent another 20 minutes pumping at an unsustainable pace, and when Liz finally arrived to take us to the rest of the team at the Sakata School, we had watered less than 10% of the field. As we said our goodbyes to the farmers we began to realize how difficult this was for them. Only one farmer was a man, and the majority of the women, smiling across from us in thanks, were in their 60’s and 70’s, an age where they should have been sharing their wisdom with younger generations, not doing backbreaking labor in the fields. If our group of young, reasonably fit people, could only water a tenth of the field while working at breakneck pace, how hard must it be for these older women to inundate the entire field once a week? Before we left Frank wanted us to see some of the fruits of the hard work that the farmers had been putting in over the last two years. He took us to the house of one of the younger women in the collective. She had a thatched roof on her house, which leaked terribly during the rainy season.

Joined by Enoch and Tory, who had come from the CBCC open house, our group spent another 20 minutes pumping at an unsustainable pace, and when Liz finally arrived to take us to the rest of the team at the Sakata School, we had watered less than 10% of the field. As we said our goodbyes to the farmers we began to realize how difficult this was for them. Only one farmer was a man, and the majority of the women, smiling across from us in thanks, were in their 60’s and 70’s, an age where they should have been sharing their wisdom with younger generations, not doing backbreaking labor in the fields. If our group of young, reasonably fit people, could only water a tenth of the field while working at breakneck pace, how hard must it be for these older women to inundate the entire field once a week? Before we left Frank wanted us to see some of the fruits of the hard work that the farmers had been putting in over the last two years. He took us to the house of one of the younger women in the collective. She had a thatched roof on her house, which leaked terribly during the rainy season. During those three or four months, which ironically helped to sustain most of her fellow villagers, she and her children lay bundled up together on the floor in one corner of the house, trying to stay dry and away from the pools, puddles and streams that formed across most of their home. As we walked inside we saw several large sheets of metal in one corner of the main room. We asked her what they were and she told us that she was using the money she was earning from being a part of the irrigation collective to buy pieces of sheet metal for a new iron roof. She told us that she should have enough pieces by next year to finish the roof and that soon her family would not have to deal with puddles of water inside their home.

During those three or four months, which ironically helped to sustain most of her fellow villagers, she and her children lay bundled up together on the floor in one corner of the house, trying to stay dry and away from the pools, puddles and streams that formed across most of their home. As we walked inside we saw several large sheets of metal in one corner of the main room. We asked her what they were and she told us that she was using the money she was earning from being a part of the irrigation collective to buy pieces of sheet metal for a new iron roof. She told us that she should have enough pieces by next year to finish the roof and that soon her family would not have to deal with puddles of water inside their home.

Finally, I was able to fully enjoy and experience everything that was going on around me through my own eyes, not through the lens of a camera, or viewed through the screen of my phone. When an elephant was looking me in the eye from a few feet away I was able to look right back into her eyes and see her quiet intelligence because I wasn’t scrambling to get a picture.

Finally, I was able to fully enjoy and experience everything that was going on around me through my own eyes, not through the lens of a camera, or viewed through the screen of my phone. When an elephant was looking me in the eye from a few feet away I was able to look right back into her eyes and see her quiet intelligence because I wasn’t scrambling to get a picture.

A few weeks ago some of the hives were broken in to and the honey inside was stolen. I asked Frank Mwenjemeka, our Agricultural Officer and an avid apiarist, to ask the beekeepers what they were doing now to guard against more thievery. As they delivered their answer to him, Frank began to laugh. I asked Frank what they had said and he replied that in addition to keeping watch during the day they were going to use “juju” or magic to keep their beloved hives safe at night. Indeed, even some members of our staff retain certain beliefs in magic from their childhoods in the village. I remember Mwalabu, VIP Project Coordinator, telling us over dinner one night about the belief in magic within his own family, which prompted Liz to blurt out the immortal question “Was your uncle a wizard?!” But as strange, and at times humorous, as it may seem to us, Malawians belief in magic can take very ugly turns. There have been reports of albinos being murdered by criminal gangs and human traffickers because their bones are claimed by Witch Doctors to bring wealth, happiness and good luck.

A few weeks ago some of the hives were broken in to and the honey inside was stolen. I asked Frank Mwenjemeka, our Agricultural Officer and an avid apiarist, to ask the beekeepers what they were doing now to guard against more thievery. As they delivered their answer to him, Frank began to laugh. I asked Frank what they had said and he replied that in addition to keeping watch during the day they were going to use “juju” or magic to keep their beloved hives safe at night. Indeed, even some members of our staff retain certain beliefs in magic from their childhoods in the village. I remember Mwalabu, VIP Project Coordinator, telling us over dinner one night about the belief in magic within his own family, which prompted Liz to blurt out the immortal question “Was your uncle a wizard?!” But as strange, and at times humorous, as it may seem to us, Malawians belief in magic can take very ugly turns. There have been reports of albinos being murdered by criminal gangs and human traffickers because their bones are claimed by Witch Doctors to bring wealth, happiness and good luck. And as tragic and unacceptable as these stories are the appropriate response is not to ridicule the beliefs of the “backwards Africans,” and lecture them on what is true and what is not, which will not change anything. Beliefs in witchcraft and magic flourish in an atmosphere of fear, poverty, and disease when people look for otherworldly causes to explain the suffering that they see around them. Only when we address the poverty that plagues the region and casts a pall over everything will these anachronistic beliefs finally begin to fade away.

And as tragic and unacceptable as these stories are the appropriate response is not to ridicule the beliefs of the “backwards Africans,” and lecture them on what is true and what is not, which will not change anything. Beliefs in witchcraft and magic flourish in an atmosphere of fear, poverty, and disease when people look for otherworldly causes to explain the suffering that they see around them. Only when we address the poverty that plagues the region and casts a pall over everything will these anachronistic beliefs finally begin to fade away.

As I gazed down from Zomba Plateau that night, I wished my students could have been there to see, to understand in a visceral way that I was never quite able to explain, what energy poverty was. To see thousands of people living in darkness, unable to do even the simplest tasks once night has fallen, because luck or fate or whatever you wanted to call it, had determined that they would be born in a poor country.

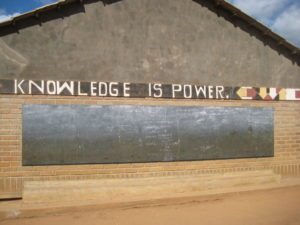

As I gazed down from Zomba Plateau that night, I wished my students could have been there to see, to understand in a visceral way that I was never quite able to explain, what energy poverty was. To see thousands of people living in darkness, unable to do even the simplest tasks once night has fallen, because luck or fate or whatever you wanted to call it, had determined that they would be born in a poor country. Students sat on the floor in dark, rusted, overcrowded classrooms. Holes in the crumbling roofs allowed shafts of sunlight to penetrate the darkness during the dry season, but also allowed water to enter during the rainy season. Faced with sitting amongst pools of muddy water, many students chose to remain at home during the rainy season, starting them on a path of failure and drop out. VIP and the Sakata School have made a tremendous amount of progress the past three years, building three brand new classrooms (with a fourth and a fifth on the way this year) and several beautiful teachers’ houses to help recruit top teaching talent.

Students sat on the floor in dark, rusted, overcrowded classrooms. Holes in the crumbling roofs allowed shafts of sunlight to penetrate the darkness during the dry season, but also allowed water to enter during the rainy season. Faced with sitting amongst pools of muddy water, many students chose to remain at home during the rainy season, starting them on a path of failure and drop out. VIP and the Sakata School have made a tremendous amount of progress the past three years, building three brand new classrooms (with a fourth and a fifth on the way this year) and several beautiful teachers’ houses to help recruit top teaching talent. But a great deal of work remains to be done. When I arrived at the school I saw hundreds of children milling about on the dusty quad. I soon learned that the school had over a thousand registered students and only 8 official classrooms. Hundreds of children are packed into each room, with many more taking classes in a nearby church or on the ground under a small cluster of trees.

But a great deal of work remains to be done. When I arrived at the school I saw hundreds of children milling about on the dusty quad. I soon learned that the school had over a thousand registered students and only 8 official classrooms. Hundreds of children are packed into each room, with many more taking classes in a nearby church or on the ground under a small cluster of trees.

On Thursday morning Liz, Stephen and I headed to Liti village for a meeting while Terra and Jordan went down in the villages to reconnect with old friends. The meeting was held in what was by far the largest building I had seen in the villages of Sakata. Built in the 90’s by another NGO, the town hall like structure is the sight of many important meetings and events in our catchment area. Today we would be meeting with the all of the chiefs from the 26 villages that we worked with, as well as the Sub Traditional Authority, a man of some importance in the Zomba region, who oversaw all of the chiefs and village headman in that area. The meeting consisted of technical matters (that I won’t bore you with) and lasted for over 4 hours because of the long and detailed questions asked by the chiefs and the Sub TA. While this tested the limits of my attention span (especially because I was merely an observer and large parts of the meeting were conducted in Chichewa) I was told afterwards by our Malwian staff how positive the intensive questioning had been. Not long ago the chiefs would have sat there silently, agreeing to whatever the wealthy Azungu proposed, not feeling confident enough to engage VIP in a healthy and constructive debate. Their questions and follow up questions were a sign that the VIP approach and emphasis on community empowerment is working. The chiefs and Sub TA and the communities they represent now feel like equal partners with VIP and are no longer content to remain passive actors. They were actively engaged in every question that was raised and every decision that was reached. It was a truly encouraging sign of a community that was determined to develop itself.

On Thursday morning Liz, Stephen and I headed to Liti village for a meeting while Terra and Jordan went down in the villages to reconnect with old friends. The meeting was held in what was by far the largest building I had seen in the villages of Sakata. Built in the 90’s by another NGO, the town hall like structure is the sight of many important meetings and events in our catchment area. Today we would be meeting with the all of the chiefs from the 26 villages that we worked with, as well as the Sub Traditional Authority, a man of some importance in the Zomba region, who oversaw all of the chiefs and village headman in that area. The meeting consisted of technical matters (that I won’t bore you with) and lasted for over 4 hours because of the long and detailed questions asked by the chiefs and the Sub TA. While this tested the limits of my attention span (especially because I was merely an observer and large parts of the meeting were conducted in Chichewa) I was told afterwards by our Malwian staff how positive the intensive questioning had been. Not long ago the chiefs would have sat there silently, agreeing to whatever the wealthy Azungu proposed, not feeling confident enough to engage VIP in a healthy and constructive debate. Their questions and follow up questions were a sign that the VIP approach and emphasis on community empowerment is working. The chiefs and Sub TA and the communities they represent now feel like equal partners with VIP and are no longer content to remain passive actors. They were actively engaged in every question that was raised and every decision that was reached. It was a truly encouraging sign of a community that was determined to develop itself. Directly across from us stood a completed brick building with a thatched roof and cloth doorway. At right angles to the finished building sat two partially completed brick structures facing each other across a courtyard created by the spacing of the buildings. Sydney’s house, to my right, had an iron sheet roof thanks to VIP, but was still many weeks from being able to house anyone. The house across from it did not yet have a roof and the entire time we sat in the courtyard with Sydney, a child sat there dully and motionless, watching us without making a sound. We soon learned from Sydney, who greeted us with a smile, that the compound housed ten people, all of whom must have lived in that one dilapidated brick building, which was roughly the size of my family’s living room.

Directly across from us stood a completed brick building with a thatched roof and cloth doorway. At right angles to the finished building sat two partially completed brick structures facing each other across a courtyard created by the spacing of the buildings. Sydney’s house, to my right, had an iron sheet roof thanks to VIP, but was still many weeks from being able to house anyone. The house across from it did not yet have a roof and the entire time we sat in the courtyard with Sydney, a child sat there dully and motionless, watching us without making a sound. We soon learned from Sydney, who greeted us with a smile, that the compound housed ten people, all of whom must have lived in that one dilapidated brick building, which was roughly the size of my family’s living room. Not only was I amazed at how he had pulled himself out of this mind numbing poverty to learn English, get accepted into an excellent secondary school and find himself poised on the verge of being accepted into university. I was amazed that he was able to smile and laugh. That he was able to keep moving forward every day when he has so much pulling him back. I was not sure what I expected to find when I came to Malawi, or what I was hoping to accomplish. But I left Sydney’s house with a more complete understanding of the indomitable nature of the human spirit and the most sincere drive to ensure that people like Sydney and his family are no longer forgotten.

Not only was I amazed at how he had pulled himself out of this mind numbing poverty to learn English, get accepted into an excellent secondary school and find himself poised on the verge of being accepted into university. I was amazed that he was able to smile and laugh. That he was able to keep moving forward every day when he has so much pulling him back. I was not sure what I expected to find when I came to Malawi, or what I was hoping to accomplish. But I left Sydney’s house with a more complete understanding of the indomitable nature of the human spirit and the most sincere drive to ensure that people like Sydney and his family are no longer forgotten. Everyone was tired as we piled into the Landcruiser for our drive to the Blantyre Airport on Wednesday morning for the team’s flight to South Africa. Liz always packs a lot into the friendship trips and our team was exhausted, both physically and emotionally. The last minute change of plans hadn’t helped the team get any more rest either. The original plan had called for the team to spend Tuesday night in Blantyre after leaving Liwonde National Park, so that they could get a full night’s rest and make their leisurely way to the airport after a late breakfast. However, the team hadn’t been satisfied with the idea of leaving Malawi like this, departing quietly like strangers in the night. At our last meeting before heading out on safari the team had asked that the plan be changed. They wanted to return to Zomba on Tuesday night so that they could take the VIP Malawian staff out to a “Thank You” dinner and give them all tokens of their gratitude and friendship. This was the first time that a friendship team had ever asked to do this, and knowing how hard the Malawian VIP staff works to make every friendship trip a success, Liz immediately agreed to the change and told the team how much the staff would appreciate it. And so we had met the staff at N’amangazi Farm on Tuesday night, and after giving a giving a short thank you speech and personalized gift bag to every VIP Senior staff member and our three translators, we headed off together one last time for a dinner under the stars.

Everyone was tired as we piled into the Landcruiser for our drive to the Blantyre Airport on Wednesday morning for the team’s flight to South Africa. Liz always packs a lot into the friendship trips and our team was exhausted, both physically and emotionally. The last minute change of plans hadn’t helped the team get any more rest either. The original plan had called for the team to spend Tuesday night in Blantyre after leaving Liwonde National Park, so that they could get a full night’s rest and make their leisurely way to the airport after a late breakfast. However, the team hadn’t been satisfied with the idea of leaving Malawi like this, departing quietly like strangers in the night. At our last meeting before heading out on safari the team had asked that the plan be changed. They wanted to return to Zomba on Tuesday night so that they could take the VIP Malawian staff out to a “Thank You” dinner and give them all tokens of their gratitude and friendship. This was the first time that a friendship team had ever asked to do this, and knowing how hard the Malawian VIP staff works to make every friendship trip a success, Liz immediately agreed to the change and told the team how much the staff would appreciate it. And so we had met the staff at N’amangazi Farm on Tuesday night, and after giving a giving a short thank you speech and personalized gift bag to every VIP Senior staff member and our three translators, we headed off together one last time for a dinner under the stars. For those of us whose stomachs were feeling homesick the chef had even prepared some Malawian attempts at personal pizzas. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of telling Sydney to try the pizza before sampling it myself, and I’m afraid that the Malawian version of it has turned him off pizza for good. Notwithstanding the pizza, we shared a wonderful last night together, laughing, telling stories, and making plans for the next time we met. One of the more interesting conversations involved the bizarre foods that are particular to Malawi and the West. On the main road connecting Zomba to Blantyre the team had seen several young boys selling mice on a stick. They couldn’t resist asking some of our Malawian staff if they had ever tried mice. While several members of the staff should their heads in disgust, most of the staff admitted, some with particular relish, that they had eaten, and indeed enjoyed, mice. Mwalabu even gave us all a detailed description (which I will spare you from here) of how the mice were caught and prepared. As we sat there shaking our heads at the strange things Malawians eat, Mwalabu compared it to westerners eating mussels. To Malawians mussels are disgusting, slimy bottom feeders that most would never consider eating. While I love mussels I knew he had a point, and couldn’t really understand why fish eggs and snails are considered delicacies by many westerners while mice are considered an uncivilized meal.

For those of us whose stomachs were feeling homesick the chef had even prepared some Malawian attempts at personal pizzas. Unfortunately, I made the mistake of telling Sydney to try the pizza before sampling it myself, and I’m afraid that the Malawian version of it has turned him off pizza for good. Notwithstanding the pizza, we shared a wonderful last night together, laughing, telling stories, and making plans for the next time we met. One of the more interesting conversations involved the bizarre foods that are particular to Malawi and the West. On the main road connecting Zomba to Blantyre the team had seen several young boys selling mice on a stick. They couldn’t resist asking some of our Malawian staff if they had ever tried mice. While several members of the staff should their heads in disgust, most of the staff admitted, some with particular relish, that they had eaten, and indeed enjoyed, mice. Mwalabu even gave us all a detailed description (which I will spare you from here) of how the mice were caught and prepared. As we sat there shaking our heads at the strange things Malawians eat, Mwalabu compared it to westerners eating mussels. To Malawians mussels are disgusting, slimy bottom feeders that most would never consider eating. While I love mussels I knew he had a point, and couldn’t really understand why fish eggs and snails are considered delicacies by many westerners while mice are considered an uncivilized meal.

Next to Susan sat Jennie and Jim Garst. The Garsts were the polar opposite of Susan as far as their experience in developing countries went. When Jennie had first received the email from her church advertising the trip to Malawi she had immediately erased it, snorting “Yeah right, I’m not going to Malawi.” But something inside of both Jennie and Jim was calling them to step outside of their comfort zone, to try new things, and they could not ignore it. There had been a lot to get used to in coming to Malawi, first and foremost the bugs and spiders which Jennie constantly battled with the help of (and I kid you not) an insecticide called “Doom.” But they had both done an incredible job on the trip, bonding with the people they met and overcoming the huge culture shock of life in Malawi. The trip would not have been the same without their humor, kindness and intelligence.

Next to Susan sat Jennie and Jim Garst. The Garsts were the polar opposite of Susan as far as their experience in developing countries went. When Jennie had first received the email from her church advertising the trip to Malawi she had immediately erased it, snorting “Yeah right, I’m not going to Malawi.” But something inside of both Jennie and Jim was calling them to step outside of their comfort zone, to try new things, and they could not ignore it. There had been a lot to get used to in coming to Malawi, first and foremost the bugs and spiders which Jennie constantly battled with the help of (and I kid you not) an insecticide called “Doom.” But they had both done an incredible job on the trip, bonding with the people they met and overcoming the huge culture shock of life in Malawi. The trip would not have been the same without their humor, kindness and intelligence. Finally, next to me sat my roommate Tom. We had bonded a great deal in our week together, often times staying up late into the night to talk, earning us the nickname “Chatty Cathy’s” from Susan, who could hear our voices through the paper thin walls. I would then stay up far later as Tom’s snores echoed inside my eardrums like cannon fire, more than once chasing me from the room to sleep in the hallway on the floor. Despite the snores, I learned so much from Tom and was glad that he was my roommate. With a PhD in Chemistry, Tom had recently created a new company, selling BioChar for use with fertilizers to heal and replenish depleted soils. Tom had come to Malawi, in part, to understand how he could use BioChar to help deeply impoverished countries like Malawi attain food security, as part of his company’s social welfare and philanthropic component.

Finally, next to me sat my roommate Tom. We had bonded a great deal in our week together, often times staying up late into the night to talk, earning us the nickname “Chatty Cathy’s” from Susan, who could hear our voices through the paper thin walls. I would then stay up far later as Tom’s snores echoed inside my eardrums like cannon fire, more than once chasing me from the room to sleep in the hallway on the floor. Despite the snores, I learned so much from Tom and was glad that he was my roommate. With a PhD in Chemistry, Tom had recently created a new company, selling BioChar for use with fertilizers to heal and replenish depleted soils. Tom had come to Malawi, in part, to understand how he could use BioChar to help deeply impoverished countries like Malawi attain food security, as part of his company’s social welfare and philanthropic component.

We said goodbye to Kondwani (Liz often sends VIP staff to the safari with the team and he may get the chance to go sometime in the near future) and loaded our bags into a small boat waiting for us at the dock and made our way over to the lodge.

We said goodbye to Kondwani (Liz often sends VIP staff to the safari with the team and he may get the chance to go sometime in the near future) and loaded our bags into a small boat waiting for us at the dock and made our way over to the lodge. After an introduction to the park and the lodge as we sipped on our ice teas and cooled ourselves off with wet towels (there had also been banana bread, but that had been stolen by a particularly mischievous monkey) we were led to our rooms. We would be staying in 4 luxury tent suites, with wrap-around wooden decks, complete with chairs and hammocks. But after a week of being covered in the dust of the village roads, and never being able to get fully clean in the shower stalls at N’amangazi Farm, everyone was most excited to see the large showers, complete with large rainwater shower heads and matching bath robes.

After an introduction to the park and the lodge as we sipped on our ice teas and cooled ourselves off with wet towels (there had also been banana bread, but that had been stolen by a particularly mischievous monkey) we were led to our rooms. We would be staying in 4 luxury tent suites, with wrap-around wooden decks, complete with chairs and hammocks. But after a week of being covered in the dust of the village roads, and never being able to get fully clean in the shower stalls at N’amangazi Farm, everyone was most excited to see the large showers, complete with large rainwater shower heads and matching bath robes. She stayed there for over 20 seconds, silently considering us, and wondering if we were worth the effort to chase away. It was a twenty seconds that seemed to both stretch on for several minutes and end far too quickly. Eventually she must have decided we were innocent enough and turned away from us and went back to grazing. I realized that I hadn’t breathed in quite a while and let it out in a long sigh, my heart pounding in my chest and a smile on my face. Matthews told us that he hadn’t had an elephant approach that close since his initial training over ten years before.

She stayed there for over 20 seconds, silently considering us, and wondering if we were worth the effort to chase away. It was a twenty seconds that seemed to both stretch on for several minutes and end far too quickly. Eventually she must have decided we were innocent enough and turned away from us and went back to grazing. I realized that I hadn’t breathed in quite a while and let it out in a long sigh, my heart pounding in my chest and a smile on my face. Matthews told us that he hadn’t had an elephant approach that close since his initial training over ten years before.

Maxwell took charge of the Sunday School students, which tickled Jim Garst to no end, when he discovered that Muhiwa had no connection with the church, but had just taken it upon himself to quiz the students and then lead them in a rousing edition of “Do As I Do” a more musical version of “Simon Says.” He the led the church in a rousing, and rather moving, rendition of “Kumbaya,” which we sang for hours afterwards after hearing it reawakened earlier memories of singing it with our schools, churches and friends.

Maxwell took charge of the Sunday School students, which tickled Jim Garst to no end, when he discovered that Muhiwa had no connection with the church, but had just taken it upon himself to quiz the students and then lead them in a rousing edition of “Do As I Do” a more musical version of “Simon Says.” He the led the church in a rousing, and rather moving, rendition of “Kumbaya,” which we sang for hours afterwards after hearing it reawakened earlier memories of singing it with our schools, churches and friends. Whether he is ululating loudly in celebration, doing some kind of bizarre dance that can best be described as Elaine Benes’s “dancing” from Seinfeld crossed with a goat kicking back its hind legs, or simply speaking, Bonongwe always seems to draw a crowd. Sunday was no different. While translating Liz’s sermon into Chichewa he would scream at the top of his lungs, gesticulating wildly and acting out the scene described by Liz, with wild eyes staring past the congregation into the distance, focused on something the rest of us could not see. As the sermon went on Bonongwe, now dripping with sweat from his performance, would add his own comments on to his translation, often ending with a loud “Hallelujah” to which the congregation would chant back “Amen.” Isaac Mwalabu leaned over to tell me that this is how preacher’s often delivered sermons in Malawi. Both to impress upon the flock the seriousness of God’s wrath, and to keep their attention through the long hours spent in uncomfortable pews, I supposed. Whatever his intentions, it was provocative and exciting theater and the congregation remained deeply engaged with him and Liz throughout the sermon and gave them both a standing ovation when they had finished.

Whether he is ululating loudly in celebration, doing some kind of bizarre dance that can best be described as Elaine Benes’s “dancing” from Seinfeld crossed with a goat kicking back its hind legs, or simply speaking, Bonongwe always seems to draw a crowd. Sunday was no different. While translating Liz’s sermon into Chichewa he would scream at the top of his lungs, gesticulating wildly and acting out the scene described by Liz, with wild eyes staring past the congregation into the distance, focused on something the rest of us could not see. As the sermon went on Bonongwe, now dripping with sweat from his performance, would add his own comments on to his translation, often ending with a loud “Hallelujah” to which the congregation would chant back “Amen.” Isaac Mwalabu leaned over to tell me that this is how preacher’s often delivered sermons in Malawi. Both to impress upon the flock the seriousness of God’s wrath, and to keep their attention through the long hours spent in uncomfortable pews, I supposed. Whatever his intentions, it was provocative and exciting theater and the congregation remained deeply engaged with him and Liz throughout the sermon and gave them both a standing ovation when they had finished. Judith is a 14 year old girl who first came to the attention of VIP when she won an inter-school quiz competition several years ago. It was then that we learned that Judith’s father had died when she was just five years old. Her mother then passed away a year later. Following the tragic death of her parents, Judith went to live with her elderly grandparents, who have cared for her ever since. The grandparents are the sole caretakers for several other orphans in the family as well, a job that grows harder and harder every year, as age takes it slow but inexorable toll on their bodies. When we first met Judith our staff realized how much promise she had and kept an eye on her as she moved through primary school. When she graduated from primary school and did well on her examinations, VIP supplied her with a scholarship so that she could attend Neno Girls Secondary School, over 60 miles from her home.

Judith is a 14 year old girl who first came to the attention of VIP when she won an inter-school quiz competition several years ago. It was then that we learned that Judith’s father had died when she was just five years old. Her mother then passed away a year later. Following the tragic death of her parents, Judith went to live with her elderly grandparents, who have cared for her ever since. The grandparents are the sole caretakers for several other orphans in the family as well, a job that grows harder and harder every year, as age takes it slow but inexorable toll on their bodies. When we first met Judith our staff realized how much promise she had and kept an eye on her as she moved through primary school. When she graduated from primary school and did well on her examinations, VIP supplied her with a scholarship so that she could attend Neno Girls Secondary School, over 60 miles from her home. After greetings and introductions the brother told the team that he used to live in what was once the kitchen, a small building that had no roof at all, leaving him completely exposed to the elements. Now he lived in a small two room mud hut built by Malawian 7th graders as a service project for their country’s most vulnerable citizens. When he invited the team inside they found two tiny 6 by 3 foot rooms. One was a kitchen where he now did all of his cooking over an open fire, breathing in the smoke and fumes. In the other room they found his bedroom, which was nothing but wads of extremely soiled blankets, or as Jim Garst put it, “a nest of rags.” As our team continued to talk with the siblings, they learned that they no longer grew any food, they were too old and sick to work in the fields. Nor were they able to do anything to generate any income. They were entirely dependent on assistance from the World Food Program and other food relief agencies.

After greetings and introductions the brother told the team that he used to live in what was once the kitchen, a small building that had no roof at all, leaving him completely exposed to the elements. Now he lived in a small two room mud hut built by Malawian 7th graders as a service project for their country’s most vulnerable citizens. When he invited the team inside they found two tiny 6 by 3 foot rooms. One was a kitchen where he now did all of his cooking over an open fire, breathing in the smoke and fumes. In the other room they found his bedroom, which was nothing but wads of extremely soiled blankets, or as Jim Garst put it, “a nest of rags.” As our team continued to talk with the siblings, they learned that they no longer grew any food, they were too old and sick to work in the fields. Nor were they able to do anything to generate any income. They were entirely dependent on assistance from the World Food Program and other food relief agencies. The sister’s face was so deeply lined and wrinkled with age and cares that she had to use her thumb and pointer fingers to lift the skin away from her eyes so that she could see who she was talking to. When our team gave them their gifts the brother and sister were so grateful, not just to be given all new things, but for the affirmation the gifts carried: that they mattered and that people cared about them and were willing to work with them and help them.

The sister’s face was so deeply lined and wrinkled with age and cares that she had to use her thumb and pointer fingers to lift the skin away from her eyes so that she could see who she was talking to. When our team gave them their gifts the brother and sister were so grateful, not just to be given all new things, but for the affirmation the gifts carried: that they mattered and that people cared about them and were willing to work with them and help them. Alice told the team that she never grew enough food to feed her family, and that in order to get enough food to eat she often went to the rice mill that VIP had built and picked up little grains of rice off the floor, until she had enough for that night’s dinner. When Liz had visited Alice in March she learned that Alice’s daughter had gone missing, leaving behind her two young children. When Liz asked if there was any news of her, Alice pointed to a woman who had been sitting far away from everyone, just beyond the outskirts of the conversation. Alice called her forward and introduced her as her daughter. Alice’s daughter avoided everyone’s eyes and sat there, with downcast eyes, umoving and unresponsive. It soon became clear to Liz from what Alice was saying, that her daughter had left the family to try to earn money by selling her body as a prostitute. No one on our team would comment on that decision after they returned from the villages later that night. The decision between gleaning rice piece by piece off of the floor in order to eat and becoming a prostitute to feed your family was what a former professor of mine, who taught a class on the decisions facing Holocaust victims, would have termed a “choiceless choice.” A choice beyond judgement, that we could never understand and simply pray we will never be forced to make.

Alice told the team that she never grew enough food to feed her family, and that in order to get enough food to eat she often went to the rice mill that VIP had built and picked up little grains of rice off the floor, until she had enough for that night’s dinner. When Liz had visited Alice in March she learned that Alice’s daughter had gone missing, leaving behind her two young children. When Liz asked if there was any news of her, Alice pointed to a woman who had been sitting far away from everyone, just beyond the outskirts of the conversation. Alice called her forward and introduced her as her daughter. Alice’s daughter avoided everyone’s eyes and sat there, with downcast eyes, umoving and unresponsive. It soon became clear to Liz from what Alice was saying, that her daughter had left the family to try to earn money by selling her body as a prostitute. No one on our team would comment on that decision after they returned from the villages later that night. The decision between gleaning rice piece by piece off of the floor in order to eat and becoming a prostitute to feed your family was what a former professor of mine, who taught a class on the decisions facing Holocaust victims, would have termed a “choiceless choice.” A choice beyond judgement, that we could never understand and simply pray we will never be forced to make. It was the last of the varieties of bricks mentioned that concerned the team on Friday morning. The team was very excited to create bricks, as they saw it as a quintessential Malawian task. Every young man in the village is supposed to build his own house when he comes of age, and because almost none can afford to buy bricks, bricks are constantly being formed in the villages.

It was the last of the varieties of bricks mentioned that concerned the team on Friday morning. The team was very excited to create bricks, as they saw it as a quintessential Malawian task. Every young man in the village is supposed to build his own house when he comes of age, and because almost none can afford to buy bricks, bricks are constantly being formed in the villages.

When we got there, the river was barely a stream, but in the heart of the rainy season the river can surge ten feet, making it impassable and preventing children from getting to Sakata School and villagers from accessing the nearby medical clinic. This new bridge will be a crucial artery of communication that will underlie progress across several areas of development. Our first assignment was to use a sledgehammer to crack rocks to use to in making the base of the bridge. Sydney Chikilema picked up the sledgehammer and took a few mighty swings before breaking the sledgehammer on the giant boulders that lay near the river.

When we got there, the river was barely a stream, but in the heart of the rainy season the river can surge ten feet, making it impassable and preventing children from getting to Sakata School and villagers from accessing the nearby medical clinic. This new bridge will be a crucial artery of communication that will underlie progress across several areas of development. Our first assignment was to use a sledgehammer to crack rocks to use to in making the base of the bridge. Sydney Chikilema picked up the sledgehammer and took a few mighty swings before breaking the sledgehammer on the giant boulders that lay near the river.

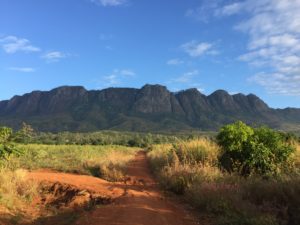

Frank said that less than 30 years ago all of these mountains were green and full of trees. But once President Banda’s dictatorship ended and Malawi became a multi-party democracy with free elections, people no longer voted for politicians who passed laws to protect the forests. Firewood was the cheapest fuel source around for heating and cooking and people began to cut down trees left and right because they simply could not afford anything else.